Translation Is The Art of Failure

- By Michael Haverty

- •

- 12 Feb, 2018

- •

"Translation is the art of failure." John Ciardi

was referring

to translation in the literary sense with his quote, but it’s

an instructive statement in the scientific world as well. Have you ever tried to explain a complex concept and only received a blank stare in return? Read a highly technical article and thought to yourself “What on earth did I just read?!” This is a common problem that hampers progress in science and

technology. Our modern society is based on how

well experts translate complex scientific concepts to non-experts in other fields

to be utilized in a simplified way.

Translation is never an easy process and as the quote suggests, is

never perfect. Although it's a struggle, learning how to translate your in-depth knowledge and

experience into an accessible form for others is a critical skill.

Translation in the manufacturing world

Think about the person that actually manufactures the light emitting diodes that form the images that your eyes see when looking at your cell phone. Because of the translation that commonly occurs in the manufacturing world that professional likely doesn’t need to know exactly how the process of electroluminescence works. Someone they work or studied with translated or distilled the important concepts of the theory into very tangible metrics for them to concentrate their focus and efforts. They use the “knobs” of their machine making the device to try to modulate the metrics that have been outlined to them as being the most important. Translation in the literary sense occurs between different languages. In the world of science and technology translation occurs between multiple people with unique experience, expertise, and responsibilities.

In reality translation is often a multi-step process in technical industries when making a product. For example, in the semiconducting industry the person responsible for making a specific part or layer of an integrated circuit is generally called a technician. Multiple technicians may be managed by an owner of the tool (sometimes called a module owner) who has a deeper understanding of the purpose and function of that part or layer, but may not know all the intricacies of operating the tool as the technician. The module owner may have only a narrow understanding of how their module fits into the related modules in the manufacturing process. That wider understanding is the responsibility of a person overseeing multiple modules manufacturing related parts of the integrated circuit (such as the front-end-of-line or back-end-of-line processing). Finally, the back-end or front-end owners report to an individual(s) in pathfinding or manufacturing with an even wider (but perhaps not quite as deep) understanding of how all sections of the integrated circuit work together and a very wide range of modules interact.

An example putting it all together

Let's discuss an example with multiple levels of translations in a typical semiconductor industry scenario. Say a technician determines their machine depositing a dielectric (insulator) typically runs for about 2 weeks before too much “junk” collects on the walls of their chamber (machine). At that point the quality of what they are producing deteriorates and they have to stop and clean the chamber (a "downtime"). The first level of translation occurs when the technician summarizes the problem and timeline to the module owner. The module owner may take a deeper dive to examine what the “junk” is and how it is forming. He or she determines if the process can be adjusted to last longer between downtimes. If it can't be adjusted, the module owner translates the findings into the critical pieces of information for the back-end owner. The back-end owner combines this with other information the module owner doesn't have access to about other tools in the processing flow. He or she estimates if that timeline impacts other tools, or if it’s necessary to try out a different dielectric material made using a different module. If the back-end owner can’t solve the problem, the issue is translated into a new technical summary for the manufacturing owner. The manufacturing owner focus is on dealing with different machines that periodically need to be taken down for cleaning and planning how many modules are requiredin parallel to keep the wafer fabrication plant always running. The manufacturing perspective is focused less on the technical details and more on throughput and quality requirements of the product.

The point of this example is to outline the translation or handshake between the different personnel from technician, to module owner, to area owner, to pathfinding or manufacturing. There is a bi-directional exchange of information between each person and that summary report or translation is unique and changes at each different level. Each person plays an important role in their translation to collect their information, distill the most important parts, and communicate it up or down the ladder for it to be effectively acted upon.

Translation as it relates to education

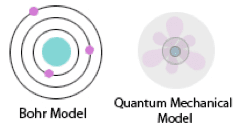

Translation occurs in the world of education in the form of curriculum development. Stop for a minute and think about your grandparents (or great grandparents depending on your age!) and the evolution of chemistry curriculum since they were in high school. They likely were taught that atoms were like a solar system with a nucleus (sun) and electrons (planets). That “model” is a translation of the work of Bohr and others. Their chemistry classes certainly didn’t contain details of quantum mechanics as it was still being refined the early 1900’s. No one had done the extra work of translating the concepts and consequences of that theory into a manner that could be easily absorbed by teenagers.

When I took chemistry in the early 90’s the curriculum included more complex models of electrons flying around atomic nuclei in clouds that looked like spheres, dumbbells, or figure 8's. That “model” is a translation of the work of Schrodinger and the complex concept of s and p orbitals of quantum mechanics. The critical aspect of the model translation is that they were presented in an easily tractable manner that I could understand without having to solve a single electron wave function.

My high school chemistry teacher Mr. Mester thought I looked bored in his class so he gave me a copy of "In Search of Schrodinger’s Cat" to read. The book was a good read because it translated more complex quantum mechanical concepts into a form on the written page that I could easily digest at that age. By the time my kids are in high school, I’m sure many more of the concepts that I struggled through in that book will be presented in an easy-to-understand manner in their senior classes.

This progression of knowledge over time is due to the theorists, writers, and educators who through careful study understand a topic in-depth, take out the most salient and relevant points, then find a way to translate or present them to someone with less knowledge than them in an accessible manner. To put a finer point on it, the actual book “In Search of Schrodinger's Cat” is a great example as a first step in translation of a complex college-level curriculum into something that a high school teenager could understand.

Why all this talk of “translation”?

As previous readers of this blog know I’m a modeler and theoretician who throughout my career has used modeling in research and development. I’ve screened new materials and chemistry and optimized them to improve the properties of the products that we all use every day. You may wonder why, I'm spending all this time talking about translation? Basically, I’ve spent my entire career translating complex atomic-scale and quantum mechanical theories into modeling software outputs and then into meaningful results and recommendations for my experimental partners. I can’t claim to have coined the term “translator” as it relates to modelers and the role they play straddling the line between theory and experimentalists. That was done by the European Materials Modeling Council as part of a new thrust. I came across that thrust last year through a friend’s recommendation and have been asked to give a talk at their 2018 summer conference and also train other “translators”. I think the concept of the “translator” is intriguing. It's helpful as a scientist to think of what you are doing as translating when trying to transfer your knowledge and learnings to someone else. For that reason I want to promote the idea of the translator and develop it further.

What does it take to be a good translator?

To borrow a phrase from a colleague, being a good translator requires a combination of pragmatism, humility, and technical excellence. I’ve known many brilliant experimentalists, theoreticians, and modelers in my career. In many cases the value of what they produced was difficult to appreciate because, to be blunt, they sucked at translating their ideas and work into a format for others to easily grasp and act upon. When working inside a team of experts, in-depth highly technical debates of the right and wrong way to think about things are instructive and useful. To make an impact however those outcomes (modeling results, theories, ideas, etc.) need to be distilled, simplified, and translated to someone with a different knowledge base to put them into practice and action. If you are lucky someone in your audience has the right combination of intellect, knowledge, and experience working with poorly molded ideas to spot the hidden potential in the fog of how your ideas are presented. However, you can’t always rely on those geniuses being in your audience to transcend the details and see the bigger picture. It’s your responsibility to be the artist. Draw your own picture by translating your learning in a way that a non-expert can understand and how best to use it.

Missed Opportunities

I’ve seen many brilliant, powerful, and sometimes elegant pieces of work or software in my career that unfortunately were missed opportunities. I’ve admired and appreciated the months/years of thought, design, and development that went into creating them. However, in many cases I’ve lamented that I knew in its current form the work's impact wouldn't match its potential for a variety of reasons. Sometimes the developer or scientist failed to look beyond their perspective or lacked the experience to understand how it would be used in the real world. At times they were too focused on the currentmethodologybuzzword of the day and didn’t grasp how to convert it into something useful. I've even seen people be “too” good at the translation process for executives and managers and forget about the engineer or scientist that will actually do the work. Many times I’ve had to disappoint an excited manager or executive and tell them the tool or method their were sold as the magic bullet completely missed its mark when it was actually tested. Don’t forget that as a translator, your own humility is just as critical as your pragmatism and technical excellence.

Take a step back

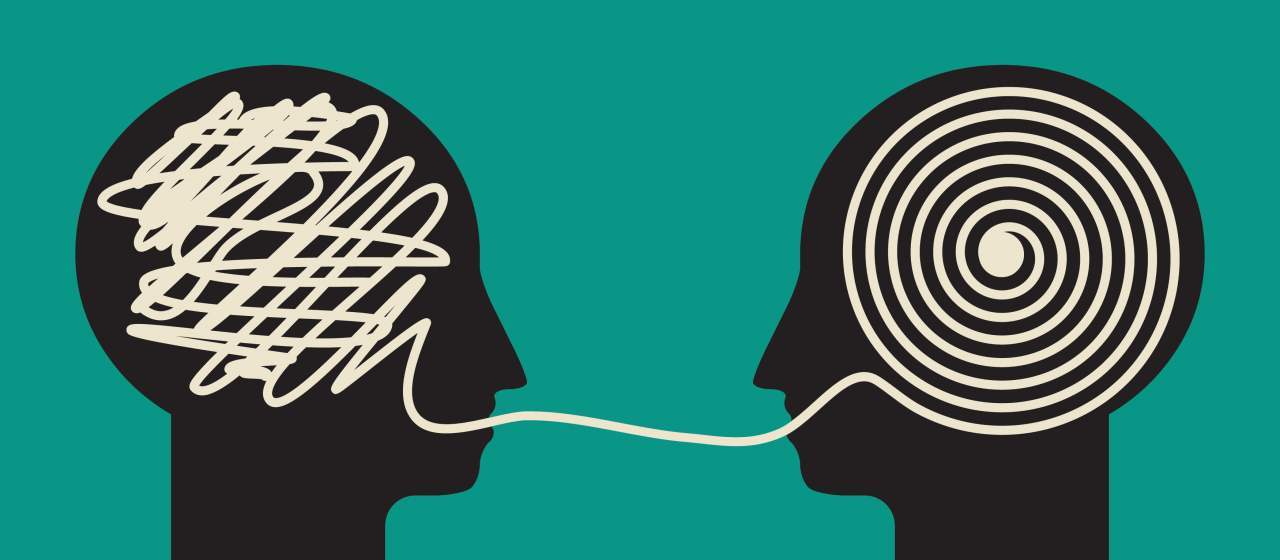

Take a step back is one of my favorite phrases. I’ve seen that many highly educated and driven people do something closer to "transcription" than "translation". This leads to the consumer of the information being overwhelmed and not getting full value out of the technology transfer. In these cases, what is needed is to:

1. Take a step back, stop, and think about the day-to-day life of your customer/partner

2. Take a step back and remember that they don’t have the same knowledge base as you

3. Take a step back and think about how what you know can uniquely help them

4. Take a step back and think about what they know that can uniquely help you and ASK them for that help

5. Take a step back and look again at your software, results, and presentation. Now cut it down to size because most of it’s only meaningful and important to you.

6. Take a step back and using (1-5) translate what you threw out into ½ the size to be accessible and meaningful to your customer/partner. Then, translate it into ½ the size again (and maybe again and again!)

I wrote this blog because the scientific world could make quicker and wider impacts in the real world if scientists were better at translating their work. Paraphrasing the quote that I started with, translation often is a failure. Your task is to turn that failure of translation into an iterative process. Learn from your mistakes and missteps. Learn more about your customer/partner. Learn how to better target your translation. If you do eventually you will see the art in your own translation.